Using the ‘Turing Tumble’ to build on creativity and problem-solving

In the game Turing Tumble, players must use problem-solving techniques to build a path for the balls to come down a specific path, ensuring that they meet the output required by the manual book. Turing Tumble is not just a game about coordination, but rather, requires the player to plan, compose and build a path for the ball to complete. The game is engaging and interesting and the manual book included a comic for students to read as they solved each puzzle. Each level included a starting position for all the blocks as well as informing you of the pieces you would be allowed to use to solve the puzzle.

An example of one of the levels, the output needed to be alternating blue and red balls.

On the turing tumble website it states “computers are full of ingenious logic and astonishing creativity…with Turing Tumble you can see how computers work” (https://www.turingtumble.com/), through the inclusion of many pieces which have different functions, students must consider the different paths of the balls and their required output before adding pieces to the path. As students are required to piece together a path for the ball, they are involved in constructing and deconstructing a path to fulfil a specific purpose. The term ‘constructionism’ was derived from Papert (1991) and relates to the idea that children learn best when they are involved in making something themselves rather than being presented with knowledge and answers directly. Constructionism challenges the ideas of the 21st century, where students are constantly consuming knowledge and rather, invites them to be co-creators of knowledge through building and collaborating with others. While constructionism is often confused with constructivism, the two learning concepts do have a few things in common (Groff 2013), that is that authentic learning occurs when building onto prior knowledge structures in meaningful ways.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority state that “in a world which is digitised and automated, it is critical to the wellbeing of society that students can be creative and discerning decision-makers” (ACARA, 2019), through using Turing Tumble, students can experience deep knowledge and understanding of digital systems while also being involved in creating this knowledge through a hands-on approach. It is imperative also that educating students about digital technologies also includes opportunities for offline tasks, which foster curiosity, creativity, persistence and cooperation and ‘Turing Tumble’ can fulfil all of those qualities.

References:

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2019). Rationale: Digital Technologies, retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/technologies/digital-technologies/rationale/.

Donaldson, J. (2014). The Maker Movement and the Rebirth of Constructionism, Hybrid Pedagogy, retrieved from http://hybridpedagogy.org/constructionism-reborn/.

Dougherty, D. (2015). The Maker Mindset, retrieved from https://llk.media.mit.edu/courses/readings/maker-mindset.pdf.

Groff, J. S. (2013). Expanding our “frames” of mind for education and the arts. Harvard Educational Review, 83(1), 15–39.

Martinez, S. (2019). The Maker Movement: A Learning Evolution, International Society for Technology in Education.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Preface. In I. Harel & S. Papert (Eds.), Constructionism: Research reports and essays, 1985–1990, 1-23.

Using Minecraft to teach students history.

Minecraft is a game where students choose to be in different landscapes and can choose creative or survival mode to explore the virtual-world to gather resources (Zaidi 2016). Students can explore materials, create houses or building, expressing creativity as well as problem-solving when encountering a problem. Not only this, but Minecraft and other games promote student collaboration through the facing of problems which students must work through together in order to find a solution. Thomas and Brown (2007) discuss how games-based learning has provided a new and unusual space for learning through taking on different worlds.

Kuhn and Stevens (2017 p. 753) state that video games are no longer just physical software but rather a new “culture”. Video games have been seen to improve learning focus in the classroom, as well as students engagement, motivation and learning of academic content. While video games do engage students, the question of alignment across the subjects syllabuses is often posed, especially as older teachers struggle with keeping up with technology and making them relevant and educational to students.

Minecraft seems to solve some of these issues, as it is reasonably accessible and has many affordances which make it relevant to many subjects within the curriculum. For example, in the subject of stage 3 history (NESA 2016), as students learn about colonisation and immigration, students can create an environment, much like Australia before Captain Cook arrived and then show the change when Australia was colonised through the resources on Minecraft. While the virtual world may seem confusing for some teachers, Zaidi (2016) suggests that educators should experience the game themselves before teaching and setting tasks for students. As well as this, while the transmission approach is used widely through classrooms, Zaidi (2016) suggests that the game loses its novelty when teachers hold tight control rather than allowing students to express their creativity through using online games.

References:

- Arnab, S. et al. 2012. Framing the Adoption of Serious Games in Formal Education, Electronic Journal of E-learning, 10(2), 159-171.

- Gee, J.P. 2005. Good Video Games and Good Learning, Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(2), 32-37.

- Kuhn, J. & Stevens, V. 2017. Participatory culture as professional development: Preparing teachers to use Minecraft in the classroom, TESOL, Vol.8, pp. 753-766.

- NSW Education Standards Authority. 2012. History K-10 Syllabus, pp.14-23.

- Thomas, D. Brown, J.S. 2007. The play of Imagination: Extending the Literary Mind, Games and Culture, 2(149).

- Zaida, S. 2016. Minecraft in the classroom, TEACH Le Prof, March/April, p.9-12.

Using virtual reality to assist students on the Autism spectrum

Virtual reality is having the experience of things which do not really exist through the use of computers. There are a few different levels of virtual reality which differ in their involvement of self into reality, these include, fully immersive (e.g. using a head-mounted display), non-immersive, collaborative e.g. Minecraft or web-based. Dede (2009) states that immersive virtual reality involves “a willing suspension of disbelief” and therefore, sets up users in a new imaginary world. Through this, students experience forces, vibrations, movement and motions to immerse them in this new world.

People who are on the autism spectrum have differing abilities to communicate with others, VR technologies have recently gained attention for their affordances for people who are on the autistic spectrum. This is due to the ability to be able to practice their social skills, control verbal and non-verbal features on different systems and practise behaviours and the mental simulation of events to practice social problem solving (Parsons and Cobb, 2011). Through Parsons (2016) discussion, the use of VR to investigate social interactions is based on the belief that VR technologies produce authentic and realistic experiences and in this way, can form a basis for social ‘norms’.

While Virtual Reality is often seen through many games, it can be an effective way to assist student learning, through enabling students to consider multiple perspectives, being situated in a specific experience and students can learn to transfer knowledge to be applied in different situations. As well as this, it removes distractions and promotes engagement in the classroom. An example of a virtual reality program which can assist students social skills is the game Sims. In Sims, students must navigate a character around to build their city and to interact with others. While players have the freedom of what the character does, they must select from a range of common behavioural characteristics. One of the major benefits of Sims to people on the autism spectrum is it’s ability to be used collaboratively.

Virtual reality has limitless possibilities in terms of assisting students with learning difficulties. Students who are on the autism spectrum can do specific social learning and practice on virtual reality systems rather than spending resources hiring experts to assist them. As well as this, people who live rurally may not have access to applied behavioural therapist and therefore it may be a good alternative. Although, educators must be aware that ‘cybersickness’, a term derived from Davis, Nesbitt and Nalivaiki, (2014) can be a health risk of Immersive Virtual Reality, therefore, attention to the time which students are on VR systems is critical to managing cybersickness.

References:

Bradley, R., Newbutt, N. (2018). Autism and Virtual Reality head mounted displays: a state of the art systematic review, Journal of Enabling Technologies, 12(3), 101-113.

Dalgarno, B., & Lee, M. J. (2010). What are the learning affordances of 3‐D virtual environments?, British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(1), 10-32.

Dede, C. (2009). Immersive interfaces for Engagement and Learning, Science, 323, 66-69.

Parsons, S. Cobbs, S. (2011). State-of-the-art of virtual reality technologies for children on the autism spectrum, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 26(3), 355-366.

Southgate, E. (2018). Immersive virtual reality, children and school education: A literature review for teachers, DICE Report Series Number 6, 1-19.

Vesisenaho, S. et al. (2019). Virtual Reality in Education: Focus on the Role of Emotions and Physiological Reactivity, Virtual Worlds Research, 12(1), 1-15.

Has Osmo revolutionalised education?

With the growing number of diagnosed learning difficulties such as dyslexia, dysgraphia and ADHD, technology is rapidly seeking to overcome barriers to student learning. Through this, students now have more access to many different types of learning through lots of different augmented reality apps such as Osmo. Augmented reality is defined in a broad sense by “augmenting feedback to the operator with simulated cues” (Milgram et al p.283), a few other features which define augmented reality is it’s real time interaction, accurate imitations of 3D of real and virtual objects and combines real and virtual worlds.

Osmo’s website claims it is a “groundbreaking system that fosters social intelligence and creative thinking by opening up the iPad and iPhone to endless possibilities of physical play”. Theorists such as Papert, suggest that students learn best when they are involved in creating their own knowledge through constructing or deconstructing knowledge, named the “constructionist” learning theory. While there may be sufficient evidence to suggest this to be true, students learn best through multiple methods and physical manipulation of objects can be beneficial to students learning. This is especially true when considering students with ADHD, where the physical embodiment of enacting knowledge assists students to retaining motivation, engagement and enjoyment.

Osmo has 3 main functions and users must buy each program to go with their iPad/iPhone. Along with these functions are different objects which users must use in order to operate the program. For the maths program, users are provided different number tiles, the tangram program includes different shape tangram pieces, while the english word program includes letters. One of the great features of the english program is that students can place tiles of certain words under the Osmo reader and it will place the letters in order. This is an extremely beneficial feature for both young children who have difficulty placing letters in order but is also groundbreaking for students with dyslexia. This app overcomes the barriers of having to spell every word in the correct order and instead awards points when users can correctly identify letters in a word. As well as this, the tangram program is lots of fun and allows students lots of flexibility in creating their own shapes through using the skills learnt prior in the app.

Wu et al (2013) discuss the affordances and features of augmented reality programs, as typical of technological tools, Osmo and other augmented reality programs are able to engage students and revitalise typically mundane learning activities through including virtuals worlds. As well as this, students can interact with synthetic objects which can enhance their enjoyment and participation, as well as this, Wu et al (2013) state that augmented realities can “bridge formal and informal learning”, therefore maths and english practice through the app Osmo can influence students intrinsic motivation for learning these subjects and strengthen students knowledge schemas through repetitive practice in physically tangible ways.

References

- Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., Grover, D. (2014). Augmented reality in Education – cases, places and potentials, Educational Media International, 51(1), pp.1-15.

- Papert, S. 1980. Mindstorms. Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. New York: Basic books.

- Milgram, P., Takemura, H., Utsumi, A., & Kishino, F. (1994). Augmented reality: a class of displays on the reality–virtuality continuum. Proceedings the SPIE: Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies, 2351, 282–292.

- Wu, H., Lee, S., Chang, H., Liang, J. Current Status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education, Computers & Education, 62, pp.41-49.

Using Cubelets to reinforce scientific concepts through Robotics

- magnets

- distance sensor

- light sensor

“Robotics education provides learners with practical experiences for understanding technological and mechanical language and systems; accepting and adapting to constant changes driven by complex environments; and utilizing knowledge in real situations or across time, space and contexts.”

(Jung and Won, 2018 p.5).

Cubelets are a type of robotic kit where students can program the different cubes to perform certain tasks. This robotic kit is really engaging as each cube serves a different purpose and therefore, they perform differently to stimuli. For example, one of the cubes has a sensor function and when paired with the moving cube can move towards or against sensed movement. The cubes are joined together through magnetism and there is a lot of free choice in regards to what shape the cubes make provided moving cubes stay connected to a surface.

There is a lot of research in regards to robotics in education, Alimisis (2012 p.9) explains that the emergence of robotics across education has something to do with the constructionist method of education, where students learn knowledge through building and deconstructing objects to encourage deep understanding. Alongside this, is the constructivist approach sees students as active creators of knowledge who build their own knowledge schemas. The teacher is therefore the guide as students explore and create. It is easy to see why robotics has been an effective way for students to create their own knowledge through being physically involved in programming actions for a robot to perform.

Alimisis (2012) states that teachers must have explicit training before teaching robotics to students. That although robotics is a great way for students to learn about coding and programming, teachers must give careful instructions and scaffold their expectations before allowing students to control their robot how they would like to. This includes, beginning a robotics class by exploring the features of a robot and challenging students to learn basic functions. Once this has been evidenced, students can move on to transform the robotics activity to something of their choice. As well as this, Jung and Won (2018) state the importance of having robotics activities carefully thought out with links to the curricula, instructional activities and learning objectives as often the purpose of using robots can be mixed up in the instruction to students.

References:

Jung, S.E., Won, E. (2018). Systematic review of research trends in Robotics education for Young Children, Sustainability,Vol.10, pp.1-24.

Alimisism, D. (2012). Robotics in Education & Education in Robotics: Shifting focus from Technology to pedagogy, Robotics in Education, p.7-14.

Using Micro-Bits to develop computational thinking

Coding is the process of assigning a symbol to an action in order for a computer to de-code the system and perform specific functions in relation to these symbols. Computational thinking is efficient problem-solving, thinking recursively (Wing 2006 p.34), planning, learning and researching. Computational thinking is behind every action we do and the mental processes we undergo. What is important to note however is that coding and programming is NOT the same as computational thinking. Students who are competent at programming foster their computational thinking skills although the two things do not occur concurrently.

Recently, government bodies across the world have tuned into the importance of computational skills across the curriculum, this has been seen in the Australian curriculum.

The micro-bit in action, playing scissor, paper, rock with its inbuilt motion detector.

The micro-bit is a pocket-sized programmable computer (BBC) which was created to inspire creativity. In the UK the micro-bit is provided to all students who are in year seven or above to develop the new generation of “tech pioneers”. It is easy to use, as students can learn how to light up the LED’s or display a pattern without needing to know much about computers. Some of the features of the micro-bit include 25 LED flashlights which can be programmed to do different things, input and output rings to connect the micro-bit to a computer, a motion detector and a built in compass. They are a great, easily accessible piece of technology which can be used in the classroom to develop computational thinking skills through programming.

When creating solutions, students define problems clearly by identifying appropriate data and requirements. When designing, they consider how users will interact with the solutions, and check and validate their designs to increase the likelihood of creating working solutions.

Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority (ACARA)

In the subjects of mathematics, STEM, science and engineering, it is vital for students to not just acquire content knowledge but also engage in practice through programs such as the micro-bit. While the micro-bit technology may be more suited towards primary aged students, it is foundational to engaging students from a young age towards STEM based subjects. Therefore, the initial lessons which they learn about coding, later develop into computational thinking, where students are competent at solving problems efficiently and can break down large complex tasks (Wing p.33). As educators, this is what we should strive for!

References

Wing, J. (2006). Computational thinking, Communications of the ACM, 49(3), pp.33-35.

Ryu, S., Lombardi, D. (2015). Coding Classroom Interactions

for Collective and Individual Engagement, Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 70-83.

ACARA. (2019). Digital Technologies. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/technologies/digital-technologies/.

Design-based learning through SketchUp

Sketch up is a 3D design software with a wide range of drawing applications. It is used in a range of workplaces such as architecture, interior design, landscaping, engineering as well as game design. As mentioned previously, technology should teach and equip students with real-life capabilities to assist integrations into professional workplaces later on.

Design thinking is an analytic and creative process that engages a person in opportunities to experiment, create and prototype models, gather feedback and redesign things in an iterative fashion.

Razzouk and Shute pg. 2, 2013.

Design-based learning is a way to build a project through testing and evaluating the effectiveness of a model. Larillard (2012) discusses that design-based learning begins when students integrate their understandings, motivations and interests, while teachers consider how they would like their students to learn and the exact skills which they will take away. Design-based learning integrates many rich ways of learning, including critiquing one’s own ideas and making changes in order to improve a product. This process of trial and improvement through designing a product allows students to build their own resilience and broaden their problem-solving ability.

In the program SketchUp, teachers can cater to students interest through activities which include students prior experiences. Educators can ask students to use the technology to cater for a particular need e.g. designing an garden which would survive on the moon. In doing so, students must gather information and research aspects of the project which is unknown to them and through this process, the teacher may guide and challenge their ideas. Design-based learning requires students to plan and usually begins as a vague plan on how a particular place/product should look. SketchUp’s abilities to create lifelike 3D imaging allows students to visualise and experiment with their design product and then make the necessary adjustments. As the process continues, students must refine their plan and then consider how it meets the design brief.

While SketchUp is easy to access and navigate, students can not have access to it at home unless they buy the costly program themselves. But through using it in a school environment, students will then be more competent when working in jobs which require these programs.

References:

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Chapter 5 – What it takes to teach. In Teaching as a Design Science – Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology, pp. 64-81.

- Kuo, M., Chuang, T. (2013). Developing a 3D Game Design Authoring Package to Assist Students’ Visualization Process in Design Thinking, IGI Global, pp.1-13.

Using Sibelius to express creativity

In our globalised world today, one commonality which many share, is an interest in music and the stimulation and enjoyment which it provides. Over the past few years, many schools have begun investing more into arts programs as the benefits of creativity to students has begun to be seen. King (2012) discusses the importance of integrating creativity with technology as educators teach competent individuals who are equipped for the future (p.2). Through technology, he argues that students can be digital storytellers who merge interdisciplinary subjects to express and create meaning in music.

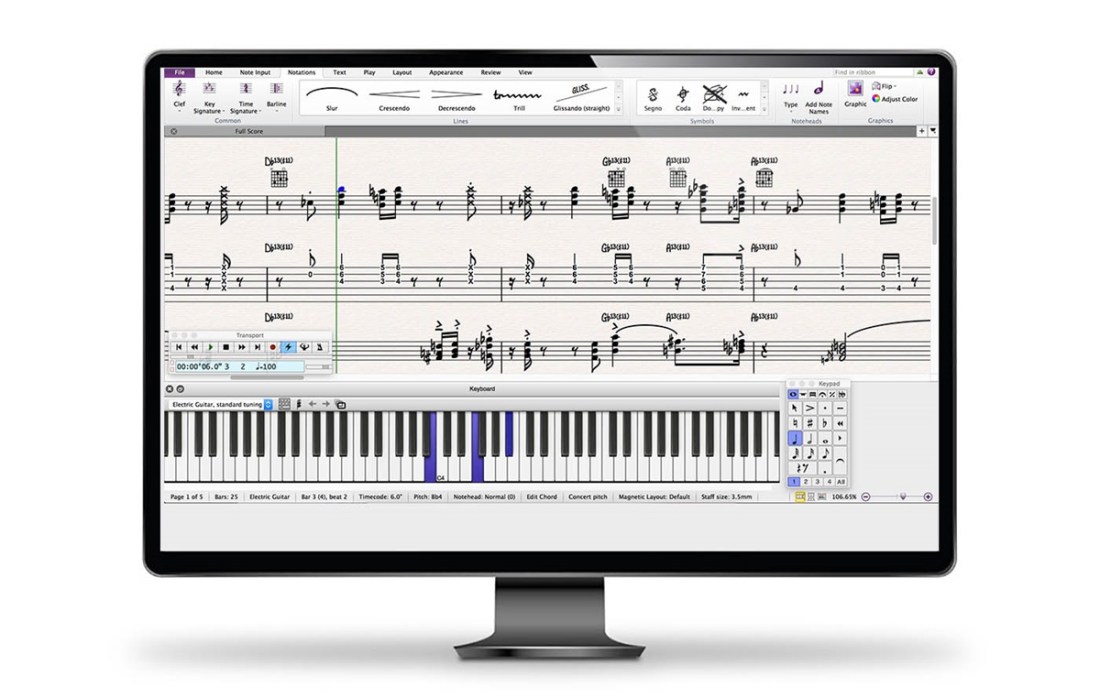

Sibelius is a music composition software, similar to the renown app “Garageband”, although has many distinct features. While Garageband can be used by the amateur musician to compose instrumental sections and layer sounds on top of each other, Sibelius requires basic music knowledge to notate and create music. However, while the disadvantage to Sibelius may be that students are required to have a basic knowledge of music, the compositions which can be created are complex and meet the demands of the real-world. Sibelius leaves more room for student creativity through the wide selection of instruments and through accessing a program which is used professionally. One problem as mentioned by Thomas (2012) is that teaching music is different to teaching music technology and many educators would feel fearful of using new technologies if they haven’t received the appropriate training for using it.

However, Rosen states that “we predict that under the right guidance and implementation, music technology courses can develop students’ self-efficacy for creative tasks and self-awareness of the creative process through experiential learning and authentic assessments” and through this, in facilitating creative thoughts, educators should build on students prior experiences and tie projects to students own interests. In this way, we see that using technology to increase and allow students to express their own creativity can form the foundation for expressing and sharing stories and meaning through audio.

Guilford (1957) states that general creativity seems to be multidimensional in nature, creativity comprises of four divergent thinking abilities: originality, fluency, flexibility and elaboration. Through this, we can see that programs such as Sibelius can assist students in using their divergent thinking abilities through notating music which allows them to share themselves, facilitates improvisation, foster opportunities for feedback meanwhile also providing parameters and limitations which remove distractions for students on technology.

- Bower, M. (2017). Technology Affordances and Multimedia Learning Effects, Design of technology-enhanced learning: integrating research and practice, Emerald Publishing, UK, 65-89.

- Guilford, J.P. (1957). Creative ability in the Arts, Psychological Review, 64(2), 110-118.

- Kiehn, M. (2003). Development of Music Creativity Among Elementary School Students, 51(4), 278-288.

King, M.D. (2012). Digital Storytelling, Principal Leadership, 13(2), 36-40. - Rosen, D et al. (2013). Utilizing Music Technology as a Model for Creativity

Development in K-12 Education, 341-344. - Thompson, D.E. (2012). Music Technology and Music Creativity: Making Connections, 25(3), 54-57.